Where'd all those durian trees come from?

Thursday, February 12, 2009 at 10:41AM

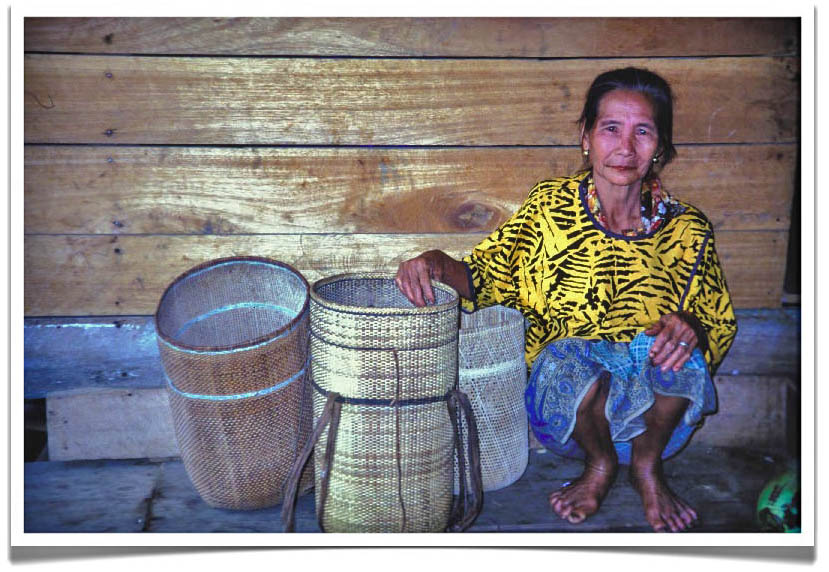

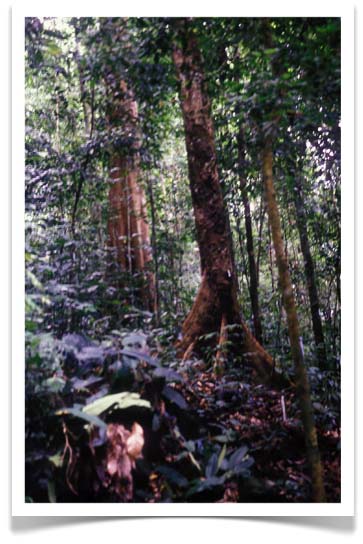

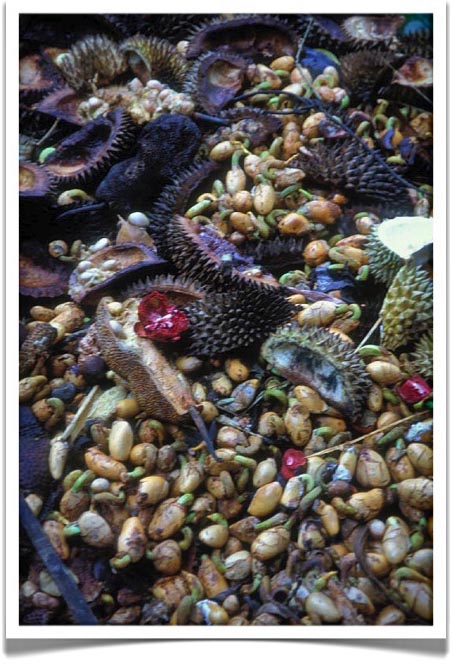

Thursday, February 12, 2009 at 10:41AM Simple question with, in this case, an obvious answer. The image below was taken behind a small lean-to ("pondok") in a managed forest orchard (see tembawang) in Bagak, West Kalimantan (see Bapaks from Bagak) during durian season. Villagers would stay in the orchard all night picking up the durian fruits that had fallen - and eating a large number of them. They'd throw the woody husks and seeds into a heap behind the pondok.

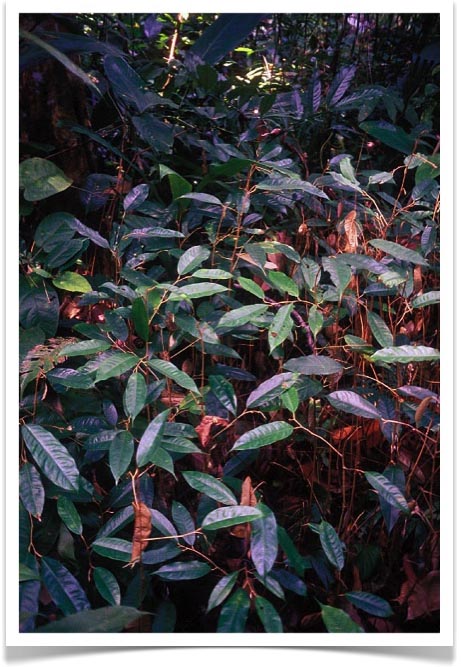

The next photo was taken behind the pondok a year later. Every one of the plants shown in the foreground is a durian seedling. These will be selectively weeded every couple of years, and, eventually, at least one of them will make it up to the canopy and start producing fruit. [NOTE: There were dozens of pondoks scattered throughout the tembawangs of Bagak during durian season. A wonderful place to spend an evening regenerating the forest].