Umberto Pacaya worked as my field assistant for three years in the Peruvian Amazon. A resident of Jenaro Herrera, Umberto was a knowledgeable matero and a wonderful person. I very much enjoyed working with him. Couple of stories. When I first started working in the flooded forests of the Ucayali River, I would occasionally use insect repellent to try to stop the onslaught of biting mosquitos. I offered some to Humberto one day, and he rubbed a little bit on the back of his neck. The next day I asked him if he wanted some more and he politely refused saying that he was never going to use that stuff again. Seems he got in trouble with his wife when he came home from the field smelling of perfume...

Umberto Pacaya worked as my field assistant for three years in the Peruvian Amazon. A resident of Jenaro Herrera, Umberto was a knowledgeable matero and a wonderful person. I very much enjoyed working with him. Couple of stories. When I first started working in the flooded forests of the Ucayali River, I would occasionally use insect repellent to try to stop the onslaught of biting mosquitos. I offered some to Humberto one day, and he rubbed a little bit on the back of his neck. The next day I asked him if he wanted some more and he politely refused saying that he was never going to use that stuff again. Seems he got in trouble with his wife when he came home from the field smelling of perfume...

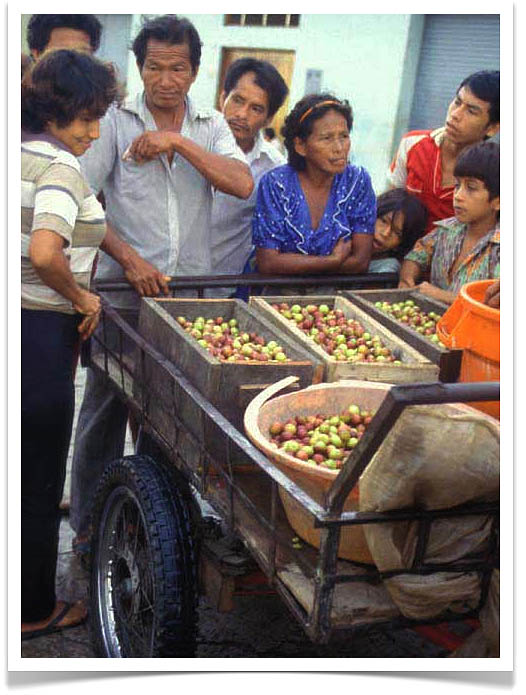

I set up a study to measure fruit production by Myrciaria dubia (see Camu-Camu) in a local ox-bow lake. We had flagged all of the sample plants, and were gradually moving the flags up as the water level rose so we could see which plants we needed to harvest. I was abruptly called back to Iquitos and left Umberto in charge of the study. The next day, it started raining like crazy and our plants began to get flooded. Umberto went out in a boat in the pouring rain, cut a bunch of poles, and propped up all of the sample plants to keep their fruits out of the water until I got back. The final results from the fruit production study are here (thx, Umberto). [NOTE: Umberto is holding a sapling of Grias peruviana, another study species from the flooded forest].

Thursday, April 23, 2009 at 2:25PM

Thursday, April 23, 2009 at 2:25PM