Rubber

Saturday, February 28, 2009 at 12:41PM

Saturday, February 28, 2009 at 12:41PM

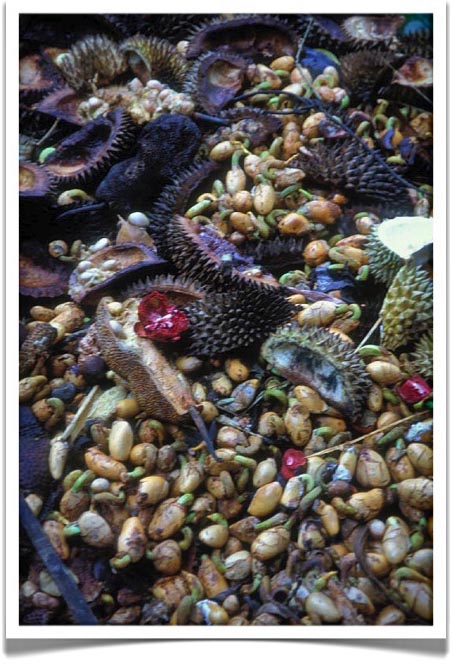

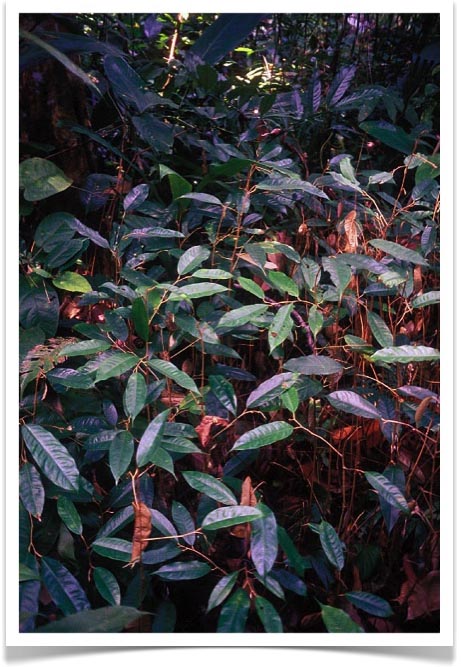

Hevea braziliensis, the source of Pará rubber, is one of the most ubiquitous trees in almost every place I have worked. It grows wild in the flooded forests of Peru where I was studying native fruits (see Regeneration Surveys, and Grias Predated), and was also quite common in the Dayak tembawangs of West Kalimantan (see Tembawang). Tapping the latex from these trees, whether cultivated or wild, provides an important source of income for rural populations throughout the tropics. [NOTE: The historical information about Pará rubber in the Wikipedia link is (embarrassingly) incorrect. Better to find a copy of J.W. Purseglove's Tropical Crops: Dicotyledons (ISBN 9780470702512) and read his thorough and extensive treatment of this important economic tree.]